Mood camera

The other day, I learned about mood camera on Jasper's blog. In the last couple of days, I've been having a lot of fun with it.

There are a lot of camera apps the allow you to take photos with a retro filter or apply it afterwards, and I've like this a lot ever since I started using Instagram (back then it was iOS only and none of my real-life friends had ever heard about it). In the last couple of years I used VSCO a lot, but have grown somewhat tired of it recently.

Mood Camera change that. It's not because of the filters, though, but because of the random mode it offers. In random mode, the app will apply one filter at random after taking a picture. Like Jasper, I removed the black and white filters from the list of random filters because I don't really like how much it changes the characteristics of an image.

What has made this fun to shoot with the most in the past few days is my rule of taking a picture of a think only once. Sometimes the added filter is quite nice and its a great picture. Sometimes its completely off and the picture does not work at all. This is close to a film experience with a dramatically shorter feedback loop. I stick to my rule of not taking another shot if the first one didn't work very strictly. This kind of makes every picture a small exercise of letting go and accepting that I cannot take a shot of everything.

While writing this post, I checked the app's website for the first time, where the author shares some guiding principles he followed while building the app. One of those reads

Encourage users to embrace uncertainty and lack of control, instead of obsessing over the perfect edit. This freedom from the pressure to produce flawless images, allows the photographer to rediscover the simple pleasure of taking photos.

The app definitely achieves that for me.

Thoughts about the future of this website

When I started to write things on the internet when I was 16 years old, it was mostly oddball thoughts of a late-developing teenager and pictures I took with my digital camera. I've tried several forms of writing for websites I maintained since. Of course, I had a link-blog back in the day when everyone wanted to be Gruber. I had german and english websites, in some of those I tried to write more professional and looked into journalism-inspired posts.

The domain you're reading this on now has been the one that was around the longest I think, and it never had a very clear concept. In the past few years, I had the feeling that I should publish mostly professional content on here, since the rest of this website is also rather professional as well (it even has a CV). I fail to do so consistently, both in terms of publishing frequency and content type.

Publishing professional content is work. I enjoy it when I do, but not every time I want to write something I want to put a lot of effort in. When writing professional content, I usually do some research and validation, go through multiple edits and think about where to share the content. And while I enjoy all of that, it feels more like work and less like a personal and creative outlet. The though of me somehow having to publish professional content on here hinders me of writing more.

Sometimes its just the silly things that I want to write but stop myself from doing. If you go through the post history of this, you'll see that this does not always work. Some silly things come through still. But a lot of it just dies, and that's sad.

Now, this domain is my name. I say that this is my personal website. I'm a professional for the better part of the day. But I'm also a dad and a husband and a son and a nerd and a somewhat goofy dude who, deep down, has no idea who he is. Is it fair for me to just allow this one part of me to shine through and only let the rest surface from time to time when I'm not able to push back for some reason? If I think about the websites that I enjoy reading the most, its always the ones that give me the feeling of getting to know a person behind it. The ones that cover the full aspect of a human.

I don't really know what this post is about and what my desired outcome is. I'm on vacation and its 5am. I woke up from a nightmare at 4am and couldn't go back to sleep afterwards (apparently some aspect of my personality is also a 10 year old boy still). I had been thinking about this topic for the past few days, so I decided this is the perfect time to start writing and see where I end up.

Maybe this is just about me giving myself allowance to be a person that plays several roles. To be an actual human that is not only professional and has to be conscious about being professional on the internet all the time. Maybe that's it. Maybe it's the part of me that got me started with writing on the internet surfacing again and this time I'm not telling it its stupid and silly and I don't want it around here. This time I'm embracing it, as a welcome guest, that can take place on this website, just as all other aspects of me, professional or not.

34

Today marks the completion of my 34th year on this planet. I don't have 34 life lessons or things I learned in the past year that I can pull out of my sleeve, unfortunately.

Here's one thing I learned, though: Even if things don't make sense, just keep going. In his famous Stanford speech, Steve Jobs said you can only connect the dots looking backwards, and he's right about that. It has been probably 10 or more years since I first heard this speech, but only now I start to understand it.

A lot of things will not make any sense if you are in the midst of them. You might wonder how any of this will ever be useful or bring your closer to where you want to be. You have to trust in yourself that it will all work out in the end. That you are capable to do something that will help you do some other thing in the future.

The thing I learned for myself is that what I think where I want to be is very limited in perspective. I don't know half of the places worth being I could end up in. They exist, but you only learn about them by doing. Some of them you create by doing a certain combination of things.

What I also learned is that things will only ever make sense for a brief period of time until they stop making sense again. I used to not like that fact, but it is a good thing, really. It means you arrived somewhere and decided you want to go further still. You're still growing.

My life advice for you (not that you asked) is to embrace the chaos, the feeling of uncertainty, the unknown.

In other news: I still don't enjoy my birthday. I don't like the idea of being celebrated for the achievement of not dying.

In my 20s, I thought this would give my character an edgy touch. Turning 30, I thought that's just how I am. Now, I think that there is an underlying reason for this. I think I struggle with the idea of people celebrating and showing affection for no reason. Non-transactional. I guess some part of me does not feel worthy of love.

So that's another uncomfortable thing to think about. But I think if I'm uncomfortable with it long enough, there might be something worthwhile coming out of it. Maybe I can enjoy my 35th birthday.

Approving by default

A couple of weeks ago, I came across a podcast episode by Ryan Peterman (which I didn't know until then, but highly recommend if you're interested in programming, organizations and career development) with Jake Bolam, who is an IC8 (Principal Engineer) at Meta. I enjoyed the entire episode a lot and would recommend listening to it, but one idea in particular stood out to me.

Jake mentioned that he always approves all Pull Requests he reviews. He goes through them, he notes his remarks, but he always approves them. That goes as far as approving something that might break production if merged unaddressed.

My initial thought was that this was crazy. We use GitHub at work and it gives you three buttons, "Approve", "Comment" and "Request Changes", probably for a reason. Why only use one of them, especially if you notice big flaws?

But as I often do with ideas that initially sound crazy to my, I gave it a shot, just to see if there is something to it. I've been approving every single Pull Request I reviewed for the past couple of weeks now. This post is about why I will continue doing it.

The team

I think initially, this caused some confusion in my peers. Usually, we would approve only if there are nitpicks that we did not feel strongly about. As soon as there was something "bigger", we usually comment (which will not allow the author to merge the PR) or request changes (which does the same, but adds a lot of red text that screams at you). There is another argument to be had about the differences of using "Comment" and "Request Changes", but this is not the place for it.

When I started doing this, I did not tell anybody, I just started. There were now instances where I commented that something would not work in production or was clearly different from how we usually do things, but approved it anyways. Coming from our current workflow, this was somewhat unintuitive. However, I did not get any personal questions about it either, so it does not seem to be such an outlandish idea after all.

Sometimes, especially in the beginning, people would re-request a review after they chose to address some of the things I mentions, following our current approach. I feel like this has happened less and less over time, probably as people became more used to this approach.

What is most interesting to me now is figuring out wether or not my peers will follow the same approach or not. This will likely be the best metric to figure out if it is useful or not.

Trust

What I like about this approach is the amount of trust it communicates. What it says is "Hey, here's a thing I think, I trust you to make the best call here, I won't block this being merges artificially because I don't think I have to control your work."

Of course there are instances where we discuss things or people want my opinion again after changing the solution, but I trust them to pull me in, if needed. It also makes the release process much faster, because everything is already approved, you can just merge when you're done.

For that to work, I have to be very clear in my communication. First, I have to make sure that the comment I'm about to add actually provides value. I have deleted a lot of comments half way in the past weeks, because I realized it was just my personal preference on a solution that would not change the outcome at all. Keeping the noise down is essential (I think that is true in general).

When I comment something, it's important that my peer has no doubt about wether what I mentioned is just a "in case you didn't know, we sometimes solve it like this but I don't feel strongly about doing it that other way here" or a "if you solve it like this, it will break production".

This approach helps me to level up the quality of my reviews a lot. If the comments are written well, this can also remove a lot of discussions where you are just trying to figure out who feels more strongly about a thing. Be design, my approval already means I feel less strongly than you. So if that's not the case, I need to make sure that is clear in my comment.

Ownership

What I like so much about this approach, in general, is that it removes this artificial safety layer. If you feel like you're working in a team that really needs to be able to block each others' Pull Requests because otherwise there will be too many issues pushed to production, this is a problem in your team, and you're not solving it by adding a process in a software you're using.

If you are commenting about topics that you think are really important, but your peers just ignore it and merge anyways, this is a great indicator that your values as a team don't align. This is a nice chance to talk about this friction and figure out a path forward that the team agrees on (please not that this may mean it will just not go your way. If this makes you feel nervous, this might also be a great indicator that you have something to work on about yourself).

I'm working exclusively with senior engineers at this point, and you might say that this would not work with mid-level or junior candidates. I think it would work even better. People grow and learn if you give them a lot of freedom and responsibility. A senior engineer telling a junior "Hey, I've spotted this thing in your code that will totally break the system, but since you now know about it, I trust you to fix it before you merge this" will make for a much more impactful learning in contrast to "Here's an issue, try to fix it and I will check in again and tell you when I think you did it right".

You might say that not everyone has that much agency or level of care. And that's fine, I get that. Depending on the team you're building, either this practice can be a nice indicator on wether or not someone fits in the team, or it does not work for your team at all. I prefer to work on teams where this works.

2024 Wrapped

2024 has been an intense year for me. It stretched me in ways I never expected: more stress, more growth, more life squeezed into twelve months than I thought possible. It felt both endless and fleeting, as if it lasted three years and only three months, all at once.

There’s plenty to reflect on, but this post isn’t about deep reflection. That will come later and I might share it or keep it private. Today, I’m simply taking inventory.

In a nutshell

- 👶 First full year with my second daughter

- 📺 Dipped my toes into DevRel video content

- ✍️ Wrote "How we built Connect" on the Gigs blog

- 🧩 Acted as a stand-in Team Lead

- 🇩🇰 Moved to Copenhagen

- 🚀 Officially moved to Engineering Management

- 💰 Gigs raised $73M Series B

- 📝 Wrote 12 articles here

- 🧑💻 Worked on 6+ side projects (proudly at $0 ARR)

- 🐥 Tried to grow my X account with limited success

I think that's the short version of the year. It mostly brought a lot of change with it, which probably made it so stressful.

I wouldn't want to trade this for a calmer year, though. I feel this constant change forced me to grow and if I'm being honest, just between you and me: I think I need that to thrive. Discipline gets me far, but real growth? That comes when I put myself in situations where I have no choice but to adapt and evolve.

I said I won't do reflection in here, so I'll keep it at that for now.

Transitioning to the Management Track

As of November 2024, I have officially transitioned to Engineering Management.

I acted as a stand-in after our previous Engineering Manager moved on for a while. In the beginning of November, I've asked my manager if we could make it official: I'm no longer an IC, for now at least1.

This post serves two purposes:

- To document this major change. It’s a personal marker for reflection, capturing how I feel now so I can revisit it in the future and see what’s changed.

- To share what I learn on the way, much as I’ve done with programming. After six months in the role, I don’t claim to have profound wisdom, but I can write about what I learned in my transition, along with tips I’ve gathered from peers, my manager, and reading along the way.

We'll start with a little bit of a personal story here, so if you’re more interested in the practical lessons than my personal journey, feel free to skip ahead.

The personal part

Looking back, I couldn’t have asked for a better start as an Engineering Manager, though I do miss being managed by my former EM, someone I deeply respect. Acting as a stand-in provided a nice safety net: It allowed me to experiment with the role without fully committing, knowing I could return to being an IC if things didn’t work out. That reduced the pressure I typically place on myself to excel right away.

I think the experience went well, but even if it hadn’t, the fallback was clear: “Thanks for keeping the ship afloat until we backfilled the role.” This freedom allowed me to focus on learning and absorbing the nuances of the job. However, I’ll admit there were limits to how fully I could embrace the role while keeping the door back to IC open. For instance, I hesitated to engage deeply in career counseling. Shifting the team dynamic in that way felt risky when there was a chance I’d soon return to being a peer.

When I officially stepped into the role, I was thrilled (and still am!). Working with people is vastly different from working with computers. Computers, as complex as they can be, are deterministic: they behave predictably if you understand their systems well enough2. Humans, however, are anything but predictable. You might leave a discussion feeling like everything is on track, only to wake up the next day and find the situation has completely shifted. Why? Maybe someone didn’t sleep well. Maybe they had a great conversation with someone who offered new perspectives. Or perhaps their mood simply changed. It could be anything. As a manager, your job is to uncover what’s changed and guide people back onto a positive trajectory. It’s an intimidating task, but it’s also one of the most fascinating parts of the role.

While it’s exciting, the job is also demanding in ways I hadn’t anticipated. As an IC, I often took programming problems home with me, but those were puzzles to solve, intellectually stimulating and self-contained. Taking people problems home is a different matter entirely. These problems affect real lives, so the stakes are higher. For me, this was a difficult adjustment. As an introvert, I ended most days completely drained. Being an IC recharged my social batteries; being an EM depletes them. I’ve had to develop strategies to manage this and prevent it from impacting my personal life too much. It’s an ongoing area of focus for me.

After six months of experimenting and taking on increasing responsibilities, I decided to fully commit to the role. I’m incredibly grateful to work in an environment where this transition was supported at every step.

What I learned

Stepping into this role, I was fortunate to receive guidance from experienced technical managers within Gigs, as well as from external resources like books and essays. There was a lot of advice, and I did my best to absorb and document it all. In here, I want to focus on the ones that seems most interesting or surprising to me.

You are now a multiplier, not an addition

The first piece of advice my manager gave me when I stepped into the role was this: Your impact is no longer additive—it’s multiplicative. This is also reflected in many books and essays on management, and it fundamentally reshapes how you think about your contributions to the team.

As an IC, you’re another pair of hands writing code. As a manager, you step back, observe, and look for opportunities to amplify the team’s effectiveness. You turn knobs and pull levers to enable the team: removing blockers, fostering collaboration, or simply helping someone see a clearer path forward. I don't think it's the title or unique skillset that allows you to do that. It’s the perspective you gain by having the possibility to step away from the day-to-day grind of shipping code.

One concept I found particularly engaging is thinking of this role in terms of measurable impact. Imagine a team of five engineers, each contributing a productivity level of 1. When one becomes a manager, the team's direct productivity drops to 4. To offset this, the manager must multiply the team’s output by at least 25% (turning that 4 into 5) to break even. Anything beyond that is a win for the team and the organization.

If anybody knows how to reliably measure productivity by the way, please let me know.

Everything is about people

This one was surprising to me. I expected a significant part of my role to involve people topics, like conducting 1-on-1s and ensuring the team could collaborate effectively without being blocked by personal issues. But I also work on non-people-related tasks, such as aligning projects with our PM, doing early technical explorations or working on team processes. Surely, not everything in this job revolves around people, right?

Nope. It does.

Every issue I’ve encountered so far ultimately traces back to people. And when you think about it, this makes sense: every decision, every challenge, and every success is the result of people working together. People bring different ideas, agendas, and perspectives to the table. Sometimes these align beautifully; other times, they clash. Resolving these conflicts becomes much easier if you've built strong relationships.

One piece of advice I received that stuck with me is this: always err on the side of people. Most people act with good intentions, even if their methods or priorities differ. The key is to understand where they’re coming from, identify the disconnects, and figure out how to move forward together. It’s not about who’s right. It’s about finding a shared "right" that aligns everyone toward the same path forward.

You have to learn to say no

The job is exciting, and if you’re like me, you’ll want to do everything. You’ll want to do a great job and dive into every opportunity that sparks your interest. But the reality is, there’s simply not enough time, and you need to communicate that.

Saying no is never easy, but it’s important. To be honest, I'm mostly writing this one down as an active reminder to myself: This is advice I’m still learning to follow. My manager once described my new role in a way that resonated: You’re now a team of one, with your own backlog. And there are always more items in your backlog than hours in the day.

There's an interesting quote by James Sexton on this when he was in the Lex Friedman podcast:

You know, the feeling at the end of the day when all your homework or all your work is done, and you just go, “Okay, it’s all done now, and I’m going to go home.” You’ll never have that feeling ever again ever. You’re just going to everyday go, “All right, it’s enough. It’s enough. I got to get out of here.”

Because with every one of these cases, you could stay up 24 hours focusing just on it. So, you have to have the discipline to go, “No, that’s it. I’m done for now. I’ve done what I could do today, and now I’m going to sit and read for a half an hour. I’m going to watch this show for a half an hour. I’m going to have this meal,” because It’s never done. So, that’s challenging. That’s a hard part of this job [...].

This isn’t a bad thing, it’s just the nature of the work. The key is to accept that you can’t do it all while ensuring the important things don’t get left behind. It’s a balancing act I’m still figuring out, but acknowledging the limits of your time is the first step.

Delayed feedback loops

Working on a product (should) come with short feedback loops. You ship something and know almost immediately if it’s broken. Within hours, stakeholders might identify areas for improvement. Within days (or at most weeks) you know whether the feature made an impact on the product and its users.

Management, on the other hand, operates on a much slower timeline. My feedback loops now span weeks, sometimes months. When I give someone feedback, they don’t instantly adapt their approach. It takes time. Maybe we need to talk a few times about the thing to get to the bottom of it. If the person acknowledges the issue as an issue and is willing to change their behavior, this process takes time as well. Progress is incremental, almost imperceptible. Then, perhaps two months later, you realize the thing you addressed isn’t happening anymore. But even then, you can’t be certain whether your input was the deciding factor.

A concrete example: a few months ago, I began documenting our technical debt. Starting this process took a few days of focused effort, and I now spend an hour here and there maintaining it. At the time, I believed the investment was worthwhile, but I couldn’t be sure. Now, months later, discussions about tech debt have expanded across the organization, and having a document has been immensely helpful. Just recently, a team member referenced it in a design document, so I assume that it is helpful.

You will look into the abyss

As an engineer, you usually have at least one organizational layer above you that puts a lot of effort into structuring the information you need. This layer ensures you can focus on your work without being overwhelmed. Transitioning into management means stepping into that layer. This means the information you have access to and have to deal with is far from structured: it’s messy, fragmented, and sometimes overwhelming.

Someone once referred to this as "the abyss," which I find to be a fitting description. I'm not sure who it was, but when they told me about it, they called it "the abyss". It’s a vortex of stakeholders, ideas, roadmaps, and priorities, all in varying states of clarity. Before anything becomes actionable for your team, this must be shaped into something coherent that aligns with the organization’s goals. There are multiple people involved in this process, but chances are that as an Engineering Manager, you’re the first technical point of contact in this process.

While this sounds intimidating, it’s also one of my favorite parts of the job. Watching an abstract idea evolve into a clear plan, passing it to the team and hearing them say "yeah, that makes sense, we understand where we're going with this and why" is incredibly rewarding.

This also does not mean the the organization I work in is particularly chaotic (I think the contrary is the case). I think this happens in every organization, eventually, naturally.

If you make a mistake, own it

There’s this myth that leaders must always know everything and never make mistakes. That’s nonsense. Every leader (every person, really) will eventually make a mistake. The real measure of a successful leader isn’t perfection. It’s ensuring you make more good decisions than bad ones over time.

When you do make a mistake, you must own it. Owning your mistakes fosters a culture of accountability. Of course, the ideal scenario would be to avoid mistakes altogether. But since that’s impossible, the next best thing is a team where mistakes are acknowledged and addressed, rather than downplayed or hidden. By taking ownership, you can often minimize the damage and even turn the experience into a learning opportunity.

This culture cannot be created solely by leaders who own their mistakes, but leaders often set the tone in an organization. As role models, their behavior carries extra weight. Leaders often have some authority, which causes them to act in a more public way. How they handle mistakes sends a message.

The takeaway is simple: act the way you want everyone else in the organization to act. Own your mistakes openly, and you’ll create an environment where accountability and growth are valued.

You will be the one making the hard decisions

Remember that time you had a coworker acting like a jerk, so you reported it to your manager? Then you went back to coding, and a few weeks later, you realized, “Oh, Bobby’s not doing that thing anymore. Nice!” Guess what: that’s your responsibility now.

It's now up to you to figure out if there’s something to the report or not. It’s your job to have the hard conversations with Bobby. And if his behavior doesn’t improve, it’s also your job to decide what happens next. Ultimately, you might be the one telling Bobby he no longer has a job because his actions are harming others3.

The safety net you had as an IC is much thinner now. Yes, you still have your own manager, and you can lean on them for guidance and support. But in a sense, as a manager, you have no human rights. You’re no longer protected from the messiness of these decisions. You’re the one responsible for resolving them.

These have only been a few of the lessons that I picked up along the way so far, but it are the ones that I could already see evidence of being true in my journey. Moving from IC to people management has been a big shift, sometimes messy, sometimes rewarding, and always a little unpredictable. I'm looking forward to learning more about this and becoming a better manager.

Footnotes

-

This does not mean that I intend to switch back any time soon. But there is the engineer/manager pendulum. ↩

-

They might not always seem deterministic. If often see myself wondering "why is that behaving this way", but I think if you're able to understand enough of the system around it and keep zooming out, eventually you'll understand and if the exact same conditions can be replicated, the computer will behave the same again. ↩

-

I should make clear that this is not a real example of what happened in my current team, but something I witnessed as an IC prior in my career. ↩

Things I enjoy about Denmark, Part 1: Electricity

I’ve recently relocated to Denmark from Germany, and even though its a direct neighbor, there are some things that are vastly different.

I want to write those things down when I notice them and while they are still new and exciting, before I get used to them.

You may have noticed that I was very optimistic and labelled this article “Part 1”, indicating that this will be an ongoing series. I really want this to become a series. Maybe it will happen. If you read this a year after it was published and there is no second part to this, please do annoy me about it.

With that out of the way, let’s jump into the first thing that I enjoy about Denmark: Electricity.

Electricity Pricing Models

In Germany, there are a few new electricity providers that offer variable electricity prices. Variable electricity prices in of itself are nothing new. Electricity is bought at an exchange and prices vary depending on supply and demand: If a lot of people need electricity (i.e. in the morning or evening), prices rise. If there is low demand for electricity (i.e. because a lot of people are at work/school), prices drop.

Historically, German electricity providers did not pass this fluctuation in price on the the customer. You usually have a contract with the provider for a set price per kWh. Those new providers allow passing on the variable price. That’s nice, because when you work from home you can just start you washing machine when prices are low and save a few bucks.

However, what’s needed to be able to profit from those prices is a way for the provider to know how much electricity you used when. In Germany, you usually have to install special hardware that allows monitoring your energy usage on your electricity meter. This has to be connected to Wifi, which prevented me from using it in my old apartment, since the electricity meter was located in the basement.

This is not the case in Denmark. Basically every provider offers both fixed and variable prices, and without the need to install anything. Why? Because in Denmark every electricity meter is a remotely read smart meter.

Smart Electricity Meters

Since the end of 2020, every household in Denmark has a smart meter installed that is operated by EnergiNet, an independent but publicly-owned company that runs the Danish energy infrastructure (by the way, the executive order that every household in Denmark should have a smart meter was issued in January of 2019, so it took about 2 years for this to be done).

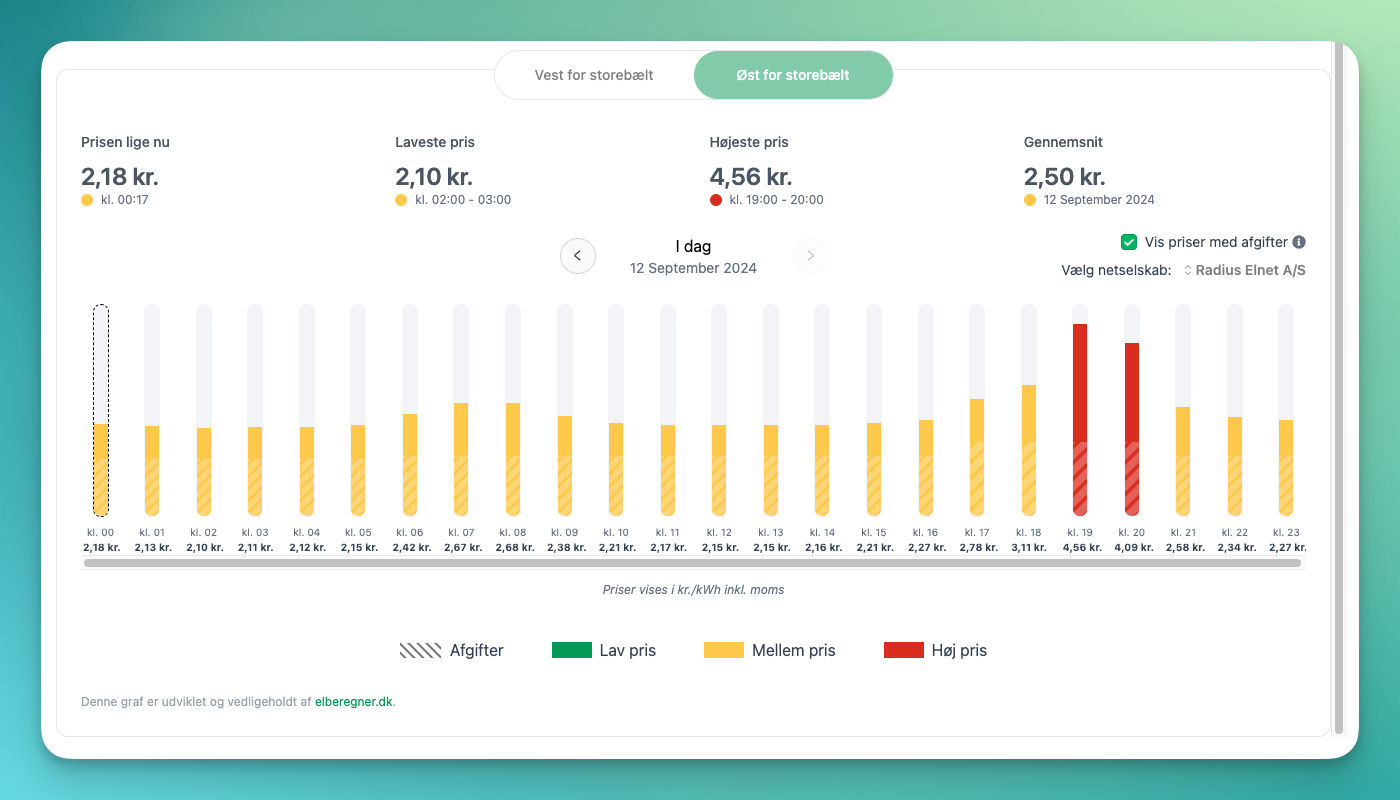

For me as a customer, that means a few things. First, I’m able to be use variable prices, since my usage will be measured anyways. I can now just check my energy providers website for todays (and tomorrows) electricity prices. For today, this tells me that prices are high in general (so maybe I want to skip laundry) and are very high in the evening (7pm and 8pm, so I would definitely want to skip laundry there).

Another cool thing is that I can easily check my current consumption in almost real time (there is usually about 24 hours of delay) online without having to walk to my meter and enter a bunch of numbers. Here’s what we’ve used to far since moving in:

Initially, we had a lot of laundry and dishes to wash, so the first few days our consumption was quite high. It’s gone down a little now.

I don’t really get much out of this currently, as our consumption seems to be on the lower end for a family of four, but it’s nice to look at it every now and then and see how we’re doing.

Availability of data

Also very interesting is the fact that all of this data is publicly available. For example, here is a dataset for the spot prices of the next day. This allows apps like Min Strøm to exist. This app not only shows the current and upcoming prices, it can even show how electricity is currently generated.

At the time of writing this (in the middle of the night), most electricity comes from wind (is sure is windy tonight) and biomass. Over the day, about 50% usually comes from solar.

For Danes and probably other Scandinavian folks, this is probably nothing new. But I was absolutely flabbergasted that this is just the norm in Denmark.

There also seems to be more you can do with your smart meter in connection to your CPR number. Unfortunately, I’m still waiting on mine, so I’ll likely come back to this topic in the future.

Relocating to Denmark

I think I’ve mentioned it here and there already, but never explicitly, and it feels like a thing I’d want to explicitly mention: We’re relocating to Denmark. While we’re not completely finished with the process, we’ve got a good chunk of it done already and I’m currently writing this from my desk in Denmark.

I’ll likely write more about this move and how I’m settling into this new life in the future, but the whole process of physically moving has been very eventful and exciting already, which justifies writing about it. It’s probably something I would be upset not to find a record of in this blog a few month or years down the line. So, let’s being.

Before moving to Denmark, we’ve lived in Cologne. We terminated our lease for the Cologne apartment in the end of April and thus had to leave it in the end of July. The lease of our apartment in Denmark started in the beginning of September, so we’ve had a month of potential homelessness to cover. Fortunately, we were able to move in with my mother in law. It was a good chance to see some family and wind down a little after packing up our lives in Cologne. It also meant living out of boxes for a month, which was exhausting. I cannot tell you how glad I am to know (with some certainty, at least) in which cupboard our glasses or my keyboards are.

My mother in law lives about an hour from our old apartment, so that also gave us the chance to perform a sort of rehearsal for the actual move: We planned to move everything in the biggest van I was legally allowed to drive (which was 3.5 Tonnes). We were not sure if a) everything would fit and b) we’d overload the van, weight-wise. If any of the two would occur, this would allow us to go around for a second time and then adapt accordingly for the move to Denmark (which, with a drive time of about 10 hours we could not just simply make in two trips).

Fortunately, everything worked out and we got everything over in one go. We also got rid of a lot of stuff in the month before the actual move, so we arrived with even less in Denmark 1. Thinking about it, fitting all belongings of a four-person-household into a small van is pretty nice from a minimalism standpoint.

Now, with all of this out of the way, let’s talk about the actual move. This must have been about the most exciting thing I’ve did in my life (apart from witnessing birth).

Dropping of the wife and kids

Since we have a cat and a dog, and the dog is too big to travel in the cabin with us, we did not want to fly all together. However, we also have two kids and only three seats in the van, so driving all together was also not possible. This left us with the constellation of me and the pets going in the van, while my wife and the kids flew over.

Our rental period started on the 1st of September, which was a Sunday, so we were to take over the apartment on the following Monday at 9 a.m. Given the restrictions from above, that left as with few possibilities, but we chose the following: The wife and kids flew over on Sunday afternoon and handled the apartment takeover on Monday. I would then drive over with the van as soon as possible afterwards.

So, on Sunday afternoon we all drove up to Düsseldorf (because the Cologne connections were mediocre) and the wife and kids hopped on to a plane to Copenhagen. Because my wife was not feeling well right before they got into security, I waited until they had successfully started, then drove back to our temporary home to pack up some last things.

They landed safe and sound in the evening and made it to their hotel which they’d live in until I was there with the van.

Getting the Van

On Monday morning, I hopped into my car and drove to Cologne. I turned up at our car shop, which offered to sell our car for us. I unregistered it online while sitting there, left the paperwork with them and tried not to cry over a such a stupid thing as a car. There were a lot of memories attached to it and it felt like giving up a bit of freedom. But, it had to go2.

I then jumped into a tram to pick up the van which I then drove back to my mother in law, again packed up some last things and waited for a friend and my brother in law to show up to help me pack it (again, a huge thank you for that!). Loading the Van took about two hours, which was faster than I anticipated.

I then tried to eat some dinner, pack up some last things and prepare everything for the next morning. Now all that was not in the Van was the animals, me, some clothes and the cat’s litter box. I failed miserably at going to sleep early, had a very bad night and woke up to my alarm at 5 a.m. the next morning.

Driving

The first thought I had when I woke up was “Oh damn, I don’t want to do this”. I then got up, made coffee, took the dog for a walk and packed my backpack. I cleaned the litter box and put it in the van together with my blanket. Then grabbed the cat and the dog and started driving at about 6:20 a.m., only about 20 minute later than I planned.

The drive was rather uneventful, for the most part. I set cruise control to 100 km/h and tried to stay behind a truck in the hope of the slipstream saving me some fuel.

At 9:10 a.m. my wife called me to tell me the handover had been done and the apartment (which she hadn’t seen in person before) was actually decent 3.

At 10:30 a.m. I took my first break. Because I had the cat and the dog with me and it was quite hot, I could not leave them in the car, so going to a shop was not possible. My provision was a large pack of Oreos and two cans of coke, because apparently I’m a 12 year old trapped in a grown-ups body.

I entered the Bremen/Hamburg area around noon and there were now a lot of customs cars observing the traffic. I was quite sure I wasn’t overloaded (we didn’t have much stuff and the tires looked fine), but did not have a scale to be sure, so my anxiety-ridden brain made sure to paint out all the scenarios where I was pulled out, weighted and had to unpack half the van. Nothing of that sort happened.

On my second break around 1 p.m. I notice Google Maps showed “Tolls” on my route, but I was avoiding ferries and was sure Denmark has only toll-free roads. Turns out there are two bridges that are actually tolled. They accept cash (Krones and Euros) and credit cards for payments. Funnily enough, my credit card had expired on the first of September which I did not notice while being in the midst of a move and I had no idea if they accepted EC cards. Luckily, I found and ATM at the rest stop and got 130 Euros (which I though would be way to much - but I’d rather be safe then sorry - but turned out to be just enough).

At about 2 p.m. I entered Denmark and was pulled out by customs right away. Anxiety brain was right back at it. The officer asked my what I was doing in Denmark and I told him I was moving here. He said “okay, exit is to the left” and that was it. I was very sure my journey in the van would end there.

I arrived at the apartment at 6:30 p.m. and stared to unpack the van (mostly by myself, while my wife was watching the kids and helping with the heavier furniture). We were done by 10 p.m., which was also way faster than I anticipated.

Returning the van

Because the van was registered in Germany, it was not possible to return it in Denmark. This meant I had to drive back to the closest German city, which is Flensburg. This also mean crossing the whole of Denmark again, which makes it the second time within 24 hours I crossed the entire country.

Me and my older daughter quickly picked up some furniture from IKEA while we still had the van and I made my way back to Flensburg at 4 p.m. My first stop wasn’t the rental company, though, but an electronics store: They had a Dyson vacuum way cheaper than in Denmark, and while I was there I picked it up. It was 7:15 p.m. by the time I left the electronics store. The plan was to go back by train and there was exactly one leaving at 8:50 p.m. So I filled the gas on the van, returned it and made my way to the train station by foot.

I arrived about half an hour before the train left with the intention to find something to eat. I did not know though, that the station in Flensburg has absolutely no stores, whatsoever. There are two vending machines, both of which only accept coins that I did not have. So my Dyson and me boarded the train to Fredericia hungry.

Luckily, Denmark had me covered with a 7/11 at the station that allowed me to grab some food (a disgusting wrap and a bar of feastables) and something to drink before boarding my train to Copenhagen

I arrived in Copenhagen at 1:20 a.m. which meant the commuter train to our apartment was not going anymore. I had to wait for a night bus, with this stupid Dyson in hand, always certain the next person passing by would just mug me for it. I finally arrived home at about 2:50 a.m., after two of the longest days ever.

This is the story if how we physically got here. We’re still in the process of obtaining a residency permit and our CPR-Numbers, so the whole thing is far from done, but we’ve made a lot of progress already.

When people asked me about the move in the past I often said “it’s going to be an adventure” and it definitely was one getting here. It taught me a lot about what I’m capable of doing.

Footnotes

-

I want to formally thank my wife for taking care of the most of this while also caring for a 6 year old and an infant, while I was mostly working. ↩

-

Denmark has a pretty aggressive tax policy towards non-electric vehicles. If we wanted to keep it, we’d have to pay about 150% of its current value in tax, which was just not economical. ↩

-

She told me again today that I did a good job picking it, which is probably the highest praise I’ve ever gotten in this regard. ↩

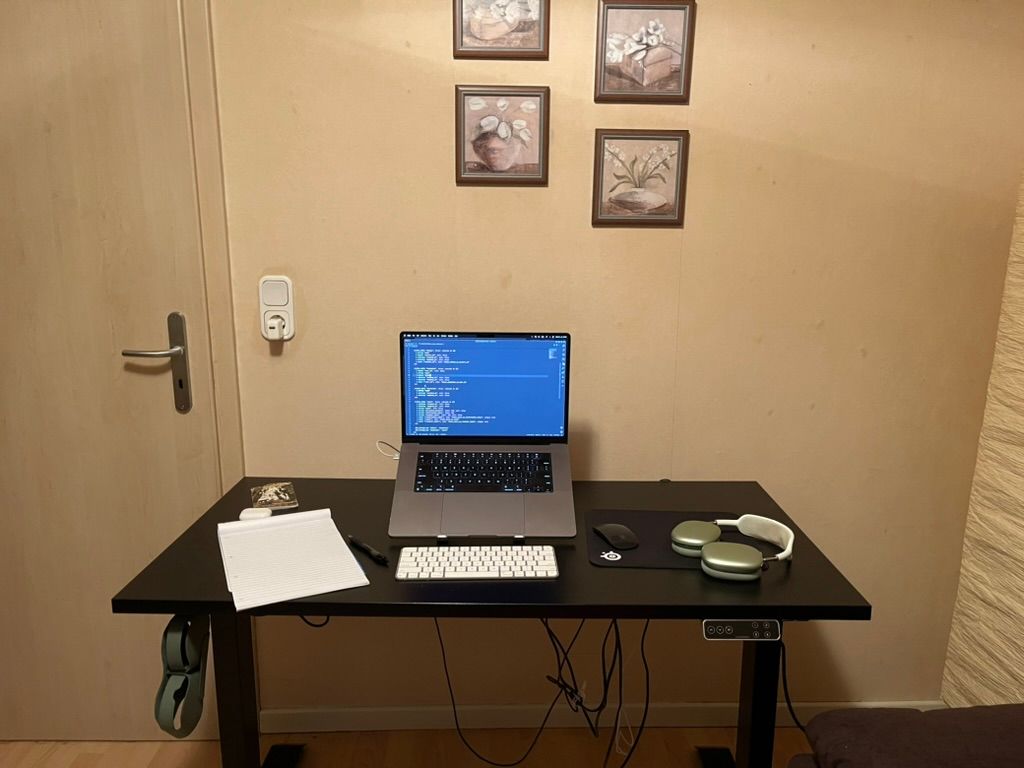

Desk - August 2024

I enjoy seeing pictures of other peoples' desks, but I rarely upload pictures of my desk myself. It's probably nice to look back over the years on where I worked with which setup (which I can do, because I have pictures, but I don't have any written documentation on it). Time to change that.

The first one is a little messy (sorry for the cables), because it's a temproary one. I'm only in this room for a month. We're staying with my mother-in-law because we're moving countries. The lease for our Cologne apartment is terminated already, but the new lease only starts in September, so we have a month in between.

A few notes on the setup:

- I didn't bother installing my widescreen monitor for the few weeks. The desk mount is heavy and on the bottom of a box. Not worth the hassle.

- Using a 2021 16" M1 MacBook Pro

- I have this mounted on a cheap Amazon laptop stand and use the Magic Mouse & Magic Keyboard to have at least some sort of posture

- Mostly using the Airpods Max while working

- I started keeping a legal pad on the side of my desk for any temporary notes. I use that a lot more than my Field Notes. The Field Notes have a higher quality, which makes me hesistan of just jotting something in. I want it to look cool.

The case for goofy side projects

It's important to make a distinction between a side project and a side hustle for this article to make sense. When I talk about side project in the following, I exclusively mean programming side projects.

Almost every programmer I know has some sort of side project going on1. If you ask a programmer what they are currently working on, there is a good chance they will tell you about their side project instead of their day job.2

I think there is two reasons for that. First, when you start out people tell you to build things that you can show around to land a job. People in the industry usually don't care about schools and degrees as much as about what you're capable of. And there is no easier way to find out than looking at a project someone did. Second, programmers tend to like programming for the sake of it. A lot of programmers don't want to stop after work or on the weekends, so they start side projects.

So you start out in your career and you go build a side project. Then you open twitter and discover other people and their side projects and one of them is making $10k a month. You decided to check out their friends on twitter and they also all have side projects that pay a lot of money. So you think: This is it. I need to have a side project that generates money and has a lot of users. One that has a purpose. And suddenly, all side projects you do become a job.

I had a few side projects like this. I started them with the intention of having a bunch of users and charge them money (spoiler: none of them ever got any users, nor did they generate any money). I was motivated in the beginning, but over time more and more anxiety crept in until it slowly became something I felt i had to do instead of something I wanted to do. I basically was under constant stress while working on them.

It was time to take a step back and ask myself what I really wanted to get out of a side project:

- Making some money on the side sounds nice, but everything comes with a cost. Generating revenue means having users. And having users means having to address other peoples needs in addition to my own. Needs of people that paid for something. It likely means doing support and fixing bugs even if I don't feel like it. It basically becomes a job, and I already have one of those that I love 3.

- Learn something new: Usually I start a side project because I want to learn. It could be a technology that is not in our tech stack at work or something I'll need in my job in the future and that I want to hit the ground running with. It could also just be pure curiosity: I wonder how X or Y works and try to find out by building it myself.

- Freedom: It's nice to just hack away, like when I first started programming. No worrying about maintainability or tests or clean code. Just mess around and see where it's going.

- Relaxation: My wife doesn't really get this, for her it's doing the same thing I do at work, after work. But it really isn't. Just coding for fun, listening to music or having a video play in the background is deeply relaxing to me.

So here I am, making the case for starting goofy side projects. Projects that have no product market fit. Projects that will not get finished. Projects that will have a $0 MRR for ever. Projects that will likely never be used by anybody. Projects you do just for fun. It's okay to have those. Capitalism has us thinking that we need to be productive, that we need to make money off of everything we do, or else it's wasted time. I'm here to make the case for wasting time.

The next time you want to do a project but catch yourself thinking about how that already exists or how nobody will pay for this, accept that. It's fine. Do it anyways.

I also have the theory that a good chunk of successful side projects start out just like that: As fun things where someone started to think "I wonder what happens if I just try..." and then just start building.

Footnotes

-

Which does not meant it's a necessity. I know great programmers that do nothing on the side. ↩

-

I think that's because a side project is something that is 100% directed by you. You usually choose your day job based on interest, but what exactly you're working on is not your decision alone. ↩

-

We're hiring, btw: https://join.gigs.com/ ↩